ℹ️NOTE: Kaskada is now an open source project! Read the announcement blog.

Many data systems claim to provide a “unified model for batch and streaming” – Apache Spark, Apache Flink, Apache Beam, etc. This is an exciting promise because it suggests a pipeline may be written once and used for both batch processing of historical data and streaming processing of new data. Unfortunately, there is often a significant gap between this promise and reality.

What these “unified” data systems provide is a toolbox of data manipulation operations which may be applied to a variety of sources and sinks and run as a one-time batch job or as an online streaming job. Depending on the framework, certain sources may not work or may behave in unexpectedly different ways depending on the execution mode. Using the components in this toolbox it is possible to write a batch pipeline or a streaming pipeline. In much the same way, it is possible to use Java to write a web server or an Android App – so Java is a “unified toolkit for Web and Android”.

Let’s look at some of the functionality that is necessary to compute features for training and applying a machine learning model. We’d like to provide the following:

- Training: Compute features from the historic data at specific points in time to train the model. This should be possible to do during iterative development of the model as well as when rebuilding the model to incorporate updated training data.

- Serving: Maintain the up-to-date feature values in some fast, highly available storage such as Redis or DynamoDB so they may be served for applying the model in production.

We’ll look at a few of the problems you’re likely to encounter. First, how to deal with the fact that training uses examples drawn from a variety of times while serving uses the latest values. Second, how to update the streaming pipeline when feature definitions change. Third, how to support the rapid iteration while experimenting with new features. Finally, we’ll talk about how a feature engine provides a complete solution to the problems of training and serving features.

If you haven’t already, it may be helpful to read Machine Learning for Data Engineers. It provides an overview of the Machine Learning terms and high-level process we’ll be discussing.

Training Examples and Latest Values

One of the largest differences between training and serving is the shape of the output. Each training example should include the computed predictor features as well as the target feature. In cases where the model is being trained to predict the future, the predictor features must be computed at the time the prediction would be made and the target feature at the point in the future where the result is known. Using any information from the time after the prediction is made would result in temporal leakage, and produce models that look good in training but perform poorly in practice, since that future information won’t be available. On the other hand, for applying the model the current values of each of the predictor features should be used.

This creates several problems to solve working with the tools in our data processing toolbox. First, we need to figure out how to compute the values at the appropriate times for the training examples. This is surprisingly difficult since most frameworks treat events as an unordered bag and aggregate over all of them. Second, we need to make this behavior configurable, so that the same logic can be used to compute training examples and current values.

Computing Training Examples

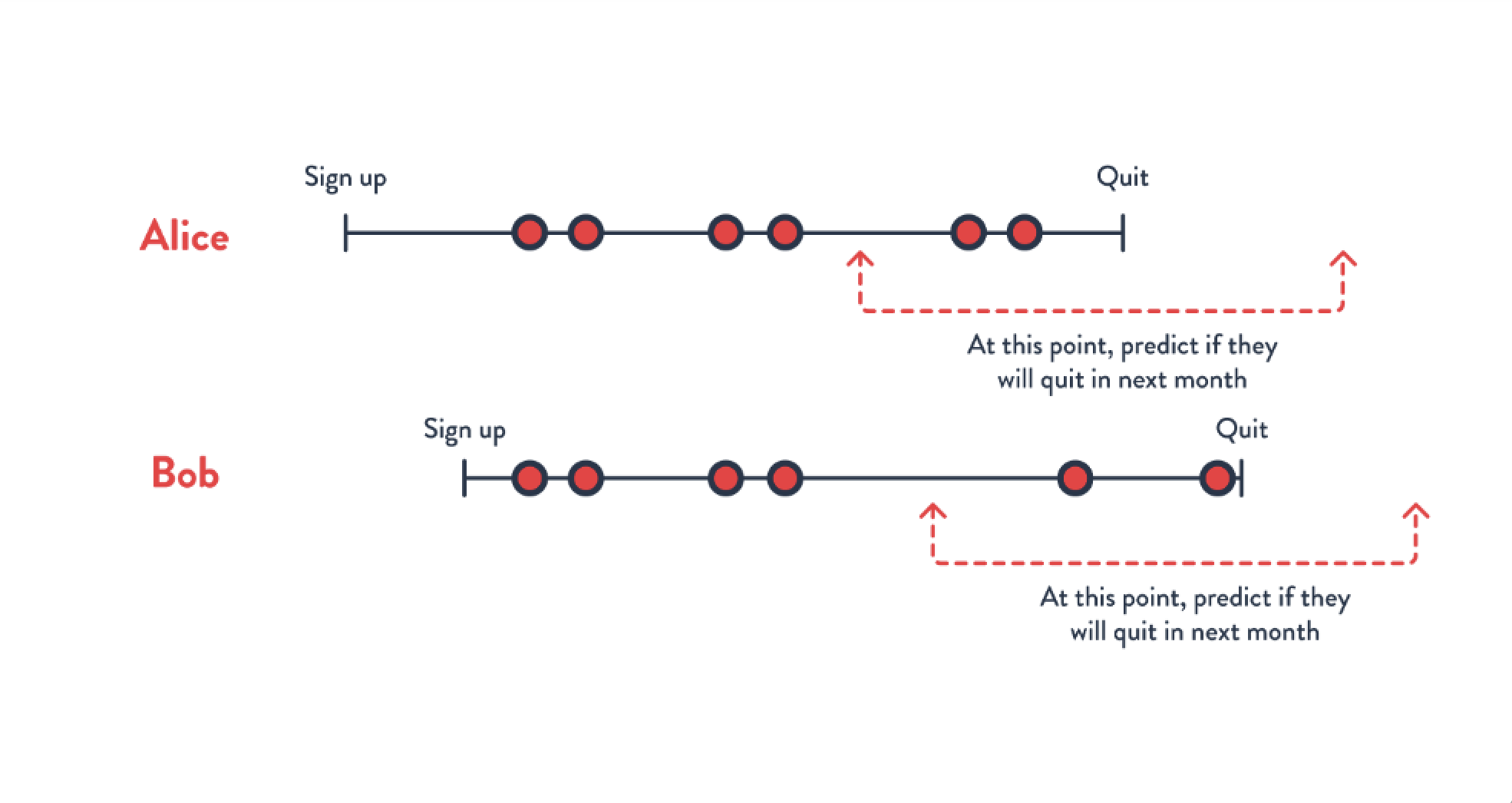

Computing training examples poses an interesting challenge for most data processing tools. Specifically, given event-based data for multiple entities – for example, users to make predictions for – we may want to create training examples 3 months before a user churns. Since each user churns at different points in time, it requires creating training examples for each user at different points in time. This is the first challenge here – ensuring that the training example for each user is computed using only the data that is available at the point in time the prediction would be made. The training example for Alice may need to be created using data up to January 5th, while the training example for Bob may need to be created using data up to February 7th. In a Spark pipeline, for instance, this may require first selecting the time for each user, then filtering out data based on the user and timestamp, and then actually computing the aggregations.

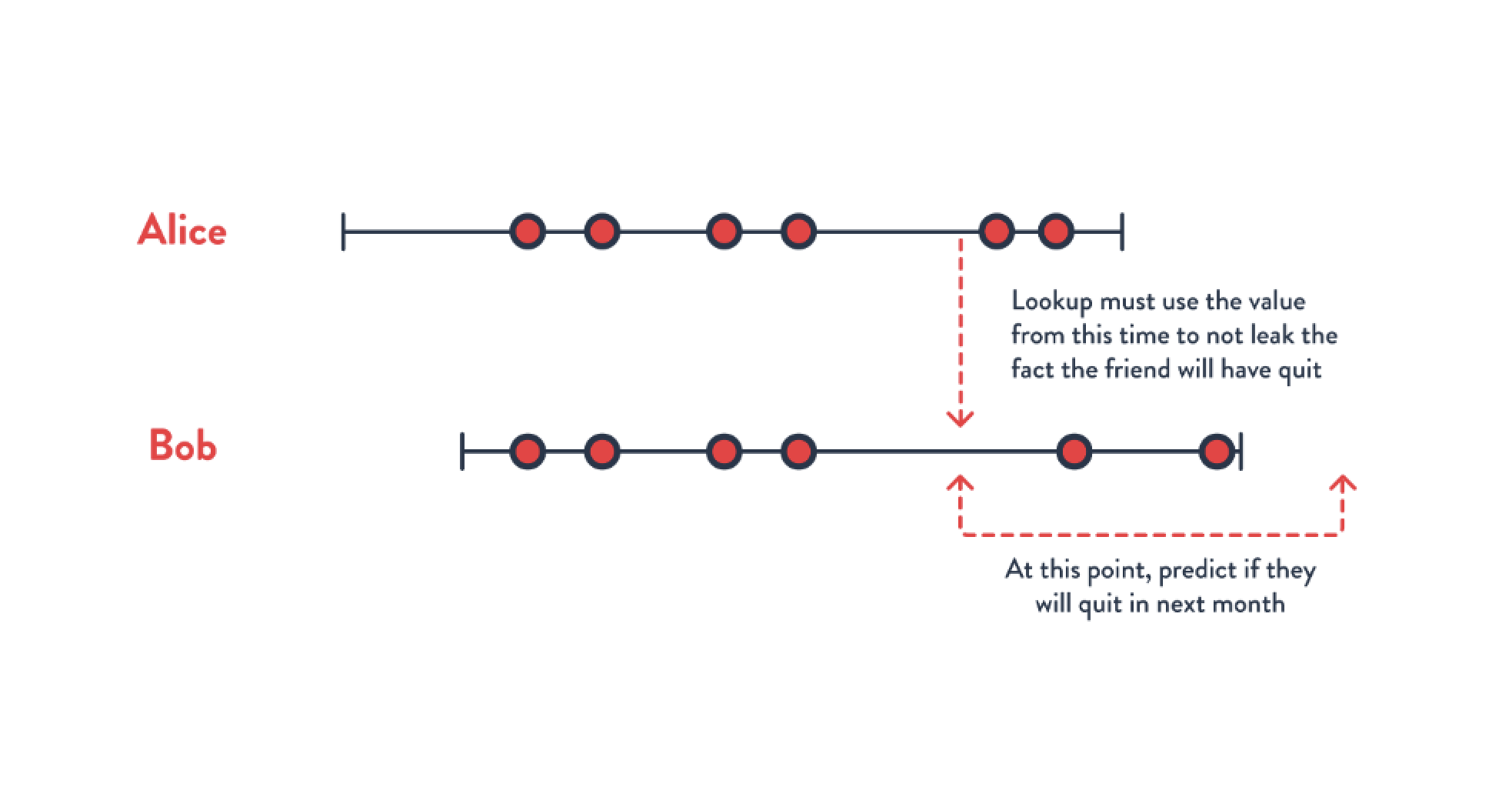

Once we’ve solved this challenge, things may get more difficult. Imagine we want to use information from the user’s social network as part of the prediction. For instance, we want to look up values from the 5 most frequent contacts, since we suspect that if they quit then the user is more likely to quit. Now we have a problem – when we compute features for Bob (using data up to February 7th), it may look up features for Alice. In this case, those computed values for Alice should include data up to February 7th. We see the simple strategy of filtering events per-user doesn’t work. If we’re using Spark, we may need to either copy all events from Alice to Bob, and then filter – but this rapidly leads to a data explosion. An alternative would be to try to process data ordered by time – but this quickly leads to poor performance since Spark and others aren’t well suited to computing values at each point in time.

Providing the ability to compute training examples at specific points in time requires deeper support for ordered processing and time travel than is provided by existing compute models. A Feature Engine must provide support for computing features (including joins) at specific, data dependent points in time.

Making it Configurable

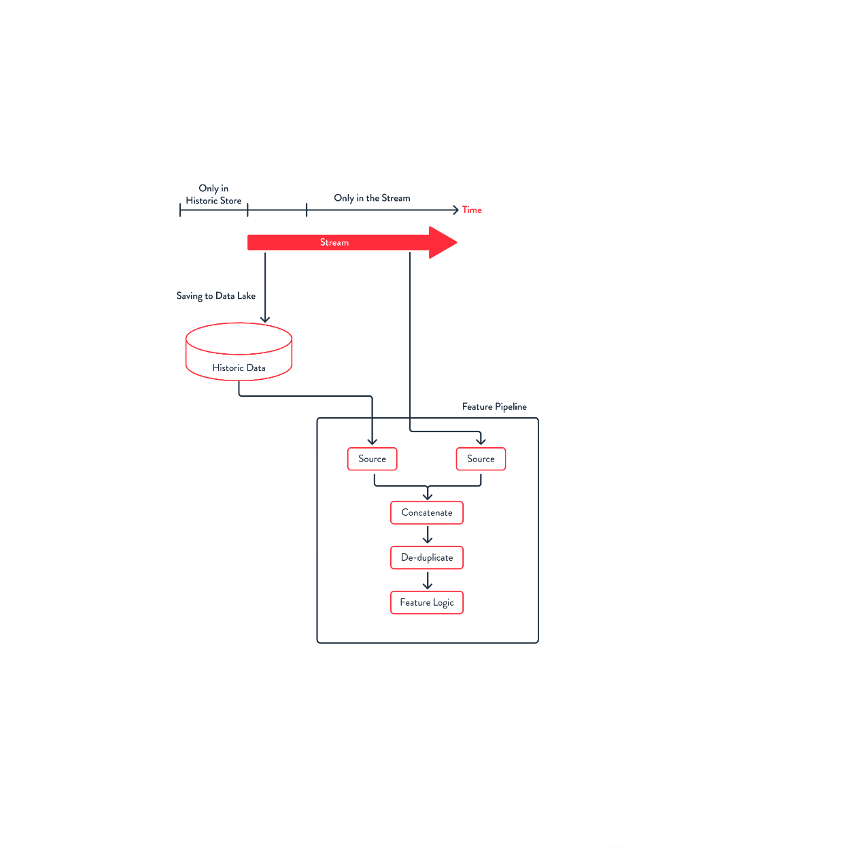

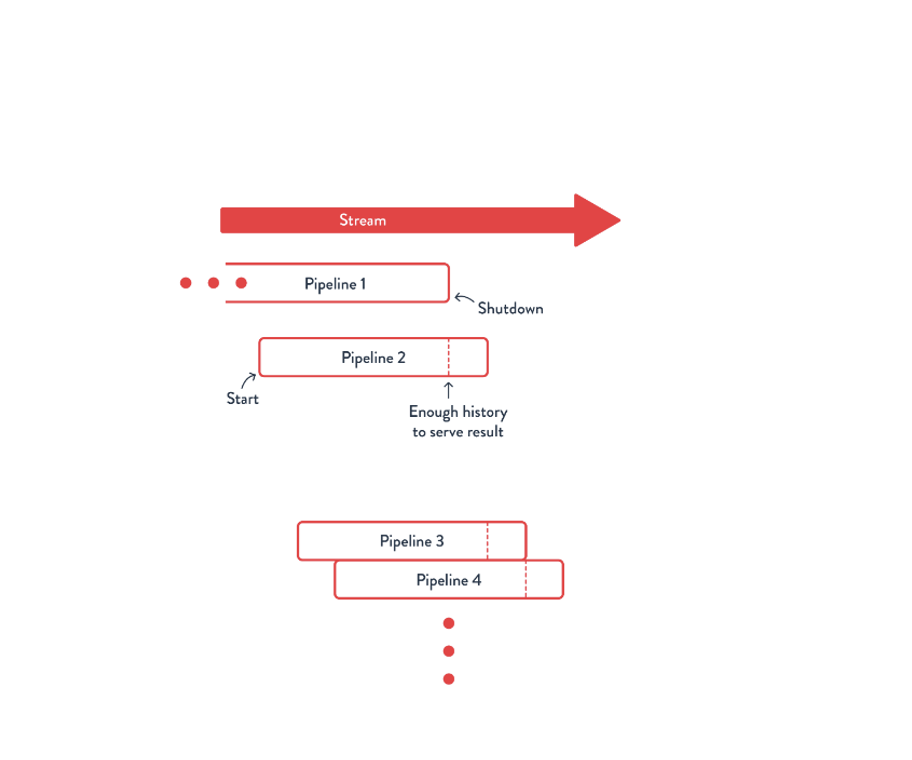

In addition to computing training examples, we need to be able to use the same logic for computing the current values when applying the model. If we’re using Spark, this may mean packaging the logic for computing the prediction features into library methods, and then having two pipelines – one which runs on historic data (at specific, filtered points in time) to produce training examples and another which applies the same logic to a stream of data. This does require codifying some of the training example selection in the first pipeline – which is something that Data Scientists are likely to want control over, since the choice of training examples affects the quality of the model. So, achieving configurability by baking it into the pipeline creates some difficulties for changing the training example selection. We’ll also see that having the streaming pipeline for the latest values creates problems with updating the pipeline. This is discussed in more detail in the next section. A Feature Engine must provide support for computing training examples from historic data and the latest results from a combination of historic and streaming data. Ideally, the choice of training examples is easy for Data Scientists to configure. Updating Stateful Pipelines Streaming pipelines are useful for maintaining the latest feature values for the purposes of applying the model. Unfortunately, streaming pipelines which compute aggregations are stateful. This internally managed–in fact nearly hidden–state often makes it difficult to update the pipeline. Consider a simple aggregation such as “sum of transaction amounts over the last week”. When this feature is added to the system, no state is available. There are two strategies that may be used. First, we could compute the initial state by looking at the last week of data. This is nice because it lets us immediately use the new feature, but may require either storing at least one week of data in the stream or a more complicated streaming pipeline that first reads events from historic data and then switches to reading from the stream. This might lead to a feature pipeline that looked something like that shown below. Note that the work to concatenate and deduplicate would depend on how your data is stored, and it may need to happen for each source or kind of data.

Alternatively, you could run the streaming pipeline for a week before using the feature. This is relatively easy to do, but rapidly breaks down if features use larger aggregation windows (say a month or a year). It also poses problems for rapid iteration – if each new feature takes a week to roll out, and data scientists are trying out multiple new features a day, we end up with many feature pipelines in various states of deployment.

A Feature Engine must provide support for computing the latest features in a way that is easily updated. The ideal strategy allows for a new feature to be used immediately, with state backfilled from historic data.

Rapid Iteration

Another thing that is easy to forget as a Data Engineer is the iterative and exploratory process of creating and improving models. This requires the ability to define new features, train models to see how they work, and possible experiment with their use in production. All of this requires providing the ability for Data Scientists to experiment with new features within a notebook. New features should be usable in production with minimal effort. A Feature Engine must allow a Data Scientist to rapidly experiment with different features and training example selections as part of iterative model creation.

Feature Engines

We saw why computing features for machine learning poses a unique set of challenges which are not solved simply by a unified model. You may choose to build this yourself on existing data processing tools, in which case the above provides a roadmap for things you should think about as you put the building blocks together. An alternative is to choose a Feature Engine which provides the mentioned capabilities out of the box. This lets you provide Data Scientists with an easy way to develop new features and deploy them, requiring minimal to no intervention from Data Engineers. In turn, this lets you focus on providing more and higher quality to Data Scientists.

Things to look for when choosing a Feature Engine:

-

A Feature Engine must provide support for computing features (including joins) at specific, data dependent points in time.

-

A Feature Engine must provide support for computing training examples from historic data and the latest results from a combination of historic and streaming data. Ideally, the choice of training examples is easy for Data Scientists to configure.

-

A Feature Engine must provide support for computing the latest features in a way that is easily updated. The ideal strategy allows for a new feature to be used immediately, with state backfilled from historic data.

-

A Feature Engine must allow a Data Scientist to rapidly experiment with different features and training example selections as part of iterative model creation.

The Kaskada Feature Engine provides all of these and more. Precise, point-in-time computations allow accurate, leakage-free computations, including with joins. One query may compute the features at selected points in time for training examples. The same query may be executed to produce only final values for serving. Queries operate over historic and streaming data, with incremental computations used to ensure that only new data needs to be processed to update feature values. Features authored in a notebook may be deployed to production with no modifications. During exploration, the Data Scientist can operate on a subset of entities to reduce the data set size without affecting aggregate values.