ℹ️NOTE: Kaskada is now an open source project! Read the announcement blog.

Part 1 — Kaskada Was Built for Event-Based Data

This is the first part in our “How data science and machine learning toolsets benefit from Kaskada’s time-centric design” series, illustrates how data science and machine learning (ML) toolsets benefit from Kaskada’s time-centric design, and specifically how Kaskada’s feature engineering language, FENL, makes defining and calculating features on event-based data simpler and more maintainable than the equivalents in the most common languages for building features on data, such as SQL and Python Pandas.

Event-based data

A software ecosystem has been growing for many years around generating and processing events, messages, triggers, and other point-in-time datasets. The “Internet-of-Things” (IoT), security monitoring, and behavioral analytics are areas making heavy use of this ecosystem. Every click on a website can generate an event in Google Analytics. Every item purchased in an online video game may send event data back to the main game servers. Unusual traffic across a secure network may trigger an alert event sent to a fraud department or other responsible party.

Devices, networks, and humans are constantly taking actions that are converted into event data which is sent to data stores and other systems. Often, event data flows into data lakes, from which it can be further processed, standardized, aggregated, and analyzed. Working with event data—and deriving real business value from it—presents some challenges that other types of data do not.

Challenges of Event-based Data

Some properties of event data are not common in other data types, such as:

-

Events are point-in-time actions or statuses of specific software components, often without any context or knowledge of the rest of the system.

-

Event timestamps can be at arbitrary, irregular times, sometimes down to the nanosecond or smaller.

-

Events of different but related types often contain different sets of information, making it hard to combine them into one table with a fixed set of columns.

-

Event aggregations can standardize information for specific purposes, e.g. hourly reporting, but inherently lose valuable granularity for other purposes, e.g. machine learning.

None of these challenges are insurmountable by themselves, but when considered together, and in the context of event data being used for many purposes downstream, it can be particularly hard to make data pipeline choices that are efficient, both from a runtime perspective as well as a development and maintenance standpoint.

Simple case study

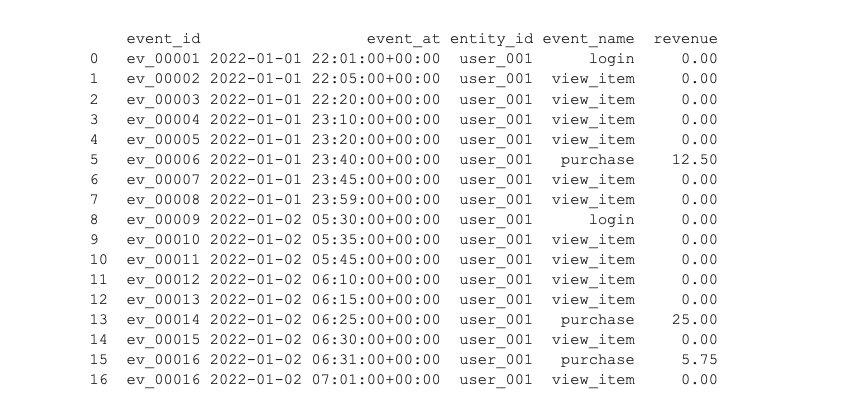

As a simple example, let’s assume we have e-commerce event data from an online store, where each event is a user action in the store, such as a login or an item sale. This event data has two downstream consumers, a reporting platform and a data science team that is building features and training datasets for predictive machine learning models. We want our data pipeline to enable both downstream customers in an efficient, maintainable way.

Our data is stored in a database table called ecommerce_event_history and looks like this:

The reporting platform needs hourly aggregations of activity, such as counts and sums of activity. The data science team is building and experimenting with features that may be helpful for machine learning models that predict future sales, lifetime value of a customer, and other valuable quantities. While some quantities calculated for the reporting platform may be of use to the data scientists, their features need to go beyond simple aggregations, and so the data scientists need a way to quickly build and iterate on features and training datasets without the help of data engineers and others who build the reporting capabilities on the same event data.

FENL vs SQL for Hourly Reporting

Kaskada’s feature engineering language, FENL, is built specifically for working with time-centric features on event-based data. Aggregations of events over time is also a core competency of FENL—aggregations can be considered a type of feature. The hourly reporting platform at our e-commerce company mainly requires simple aggregations, such as those shown below in SQL and the equivalent in FENL.

SQL

SELECT

DATE_TRUNC ('hour', event_at) as reporting_at,

entity_id as user_id,

count (*) as event_count,

SUM (revenue) as revenue_total

FROM

ecommerce_event_history

GROUP BY 1, 2

FENL

let event_count = ecommerce_event_history | count(window=since(hourly()))

let reporting_date = event_count | time_of()

let user_id: ecommerce_event_history.entity_id | last()

{

reporting_date,

user_id,

event_count,

revenue_total: ecommerce_event_history.revenue | sum()

}

| when (hourly())

The SQL aggregations are fairly straightforward, and the FENL equivalent is similar but slightly different due to FENL’s special handling of time variables and our use of the let keyword for assigning variable names within the query, for clarity and convenience. Both versions use a count() and a sum() function, and both group by user_id and date, though FENL’s grouping is implicit because user_id is the entity ID and because the hourly() function is used to specify the times at which we would like to know results. For more information on entities and the treatment of time in FENL, see the FENL language guide.

Overall, SQL and FENL are comparable for these simple aggregations, with the main trade-off being that SQL requires an explicit GROUP BY where FENL uses the time function hourly() and implicit grouping by entity ID to accomplish the same thing. In addition, if you want to have values for every hour, not just the hours that contain events, SQL requires some non-trivial extra steps to add those empty hours and fill them with zeros, nulls, etc. FENL includes all hours (or other time intervals) by default, and if you don’t want those empty intervals, a simple row filter removes them.

FENL vs SQL for ML Features

Features for machine learning generally need to be more sophisticated than the basic stats used in reporting analytics. Data scientists need to build beyond those simple aggregations and experiment with various feature definitions in order to discover the features that work best for the ML models they are building.

Adding to the case study from above, our FENL vs SQL vs Python Pandas Colab notebook takes an expanded version of the e-commerce case and builds ML feature sets that are significantly more sophisticated than the example code for hourly aggregations that we showed previously. It’s not that any single feature is particularly complicated, but the combination of hourly aggregations, like revenue total, with full-history stats, like age of a user’s account and time since last account activity, makes building the feature set as a whole more complicated.

See the example features written below in both SQL and FENL, and the notebook linked for more details and working code.

SQL

/* features based on hourly aggregations */

with hourly agg as (

select

entity_id

, event_hour_start

, event_hour_end

, event_hour_end_epoch

/* features from hourly aggregation */

, count (*) as event_count_hourly

, sum (revenue) as revenue_hourly

from

events_augmented /* the equivalent of CodeComparisonEvents in this notebook */

group by

1, 2, 3

)

/* features based on full event history up to that time */

select

hourly_agg.entity_id

, hourly_agg.event_hour_end

, hourly_agg.event_hour_end_epoch

, hourly_agg.event_count_hourly

, hourly_agg.revenue_hourly

/* features from all of history */

, count (*) as event_count_total

, sum (events_augmented. revenue) as revenue_total

, min (events_augmented.event_at_epoch) as first_event_at_epoch

, max(events_augmented.event_at_epoch) as last_event_at_epoch

from

hourly_agg

left join events_augmented

on hourly_agg.entity_id = events_augmented.entity_id

and hourly_agg.event_hour_end >= events_augmented.event_at

group by

1, 2, 3, 4, 5

FENL

# set basic variables to be used in later expressions

let epoch_start = 0 as timestamp_ns

# create continuous-time versions of inputs

let timestamp = CodeComparisonEvents | count() | time_of()

let entity_id = CodeComparisonEvents.entity_id | last ()

in {

entity_id,

timestamp,

event_count_hourly: CodeComparisonEvents | count (window=since(hourly())),

revenue_hourly: CodeComparisonEvents.revenue | sum (window=since(hourly())),

event_count_total: CodeComparisonEvents | count(),

revenue_total: CodeComparisonEvents.revenue | sum(),

first_event_at_epoch: CodeComparisonEvents.event_at | first() | seconds_between(epoch_start, $input) as 164,

last_event_at_epoch: CodeComparisonEvents.event_at | last () | seconds_between(epoch_start, $input) as 164,

}

| when (hourly())

FENL, in this example, allows us to write a set of feature definitions in one place, in one query block (plus some variable assignments for conciseness and readability). It is not a multi-stage, multi-CTE query with multiple JOIN and GROUP BY clauses, like the equivalent in SQL, which adds complexity and lines of code, and increases the chances of introducing bugs into the code.

Of course, FENL can’t simplify every type of feature definition, but when working with events over time and a set of entities driving those events, building features for predicting entities’ future behavior is a lot easier with FENL. FENL’s default behavior handles multiple simultaneous and disparate time aggregations in a natural way and joins resulting feature values on the time variable by default as well. All of this comes with syntax that feels clean, clear, and functional.

See our FENL vs SQL vs Python Pandas Colab notebook for more detailed code examples, more details, information, and example notebooks are available on Kaskada’s documentation pages.