In the last decade, advances in data analytics, machine learning, and AI have occurred, thanks in part to the development of technologies like Apache Spark, Apache Flink, and KSQL for processing streaming data. Unfortunately, streaming queries remain difficult to create, comprehend, and maintain – you must either use complex low-level APIs or work around the limitations of query languages like SQL that were designed to solve a very different problem. To tackle these challenges, we introduce a new abstraction for time-based data, called timelines.

Timelines organize data by time and entity, offering an ideal structure for event-based data with an intuitive, graphical mental model. Timelines simplify reasoning about time by aligning your mental model with the problem domain, allowing you to focus on what to compute, rather than how to express it.

In this post, we present timelines as a natural development in the progression of stream processing abstractions. We delve into the timeline concept, its interaction with external data stores (inputs and outputs), and the lifecycle of queries utilizing timelines.

This post is the first in a series introducing Kaskada, an open-source event processing engine designed around the timeline abstraction. The full series will include (1) this introduction to the timeline abstraction, (2) how Kaskada builds an expressive temporal query language on the timeline abstraction, (3) how the timeline data model enables Kaskada to efficiently execute temporal queries, and (4) how timelines allow Kaskada to execute incrementally over event streams.

Rising Abstractions in Stream Processing

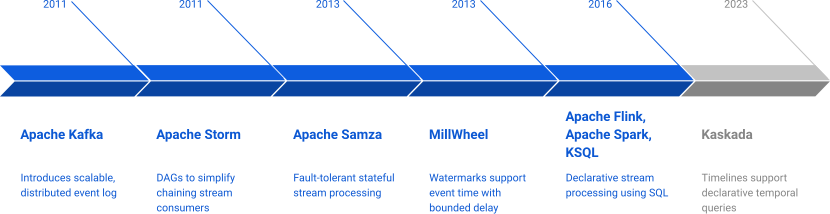

Since 2011, alongside the rise of distributed streaming, there has been a trend towards higher abstractions for operating on events. In the same year that Apache Kafka introduced its distributed stream, Apache Storm emerged with a structured graph representation for stream consumers, enabling the connection of multiple processing steps. Later in 2013, Apache Samza provided fault-tolerant, stateful operations over streams, and the MillWheel paper introduced the concept of watermarks to handle late data. Between 2016 and 2017, Apache Flink, Apache Spark, and KSQL implemented the ability to execute declarative queries over streams by supporting SQL.

Each of these developments enhanced the abstractions used when working with streams – improving aspects such as composition, state, and late-data handling. The shift towards higher-level, declarative queries significantly simplified stream operations and the management of compute systems. However, expressing time-based queries still poses a challenge. As the next step in advancing abstractions for event processing, we introduce the timeline abstraction.

The Timeline Abstraction

Reasoning about time – for instance cause-and-effect between events – requires more than just an unordered set of event data. For temporal queries, we need to include time as a first-class part of the abstraction. This allows reasoning about when an event happened and the ordering – and time – between events.

Kaskada is built on the timeline abstraction: a multiset ordered by time and grouped by entity.

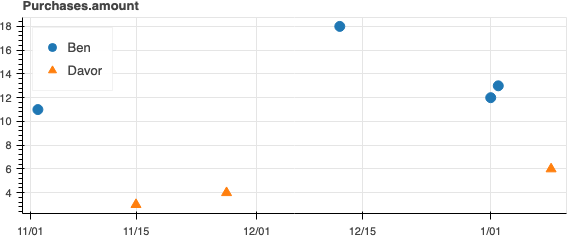

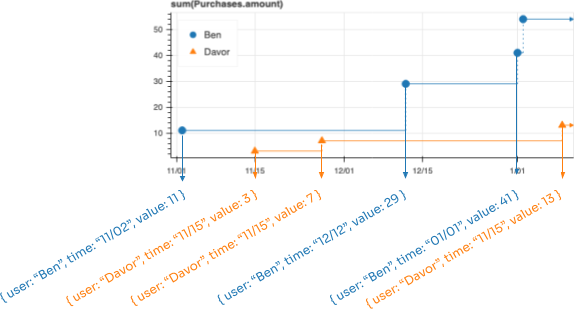

Timelines have a natural visualization, shown below. Time is shown on the x-axis and the corresponding values on the y-axis. Consider purchase events from two people: Ben and Davor. These are shown as discrete points reflecting the time and amount of the purchase. We call these discrete timelines because they represent discrete points.

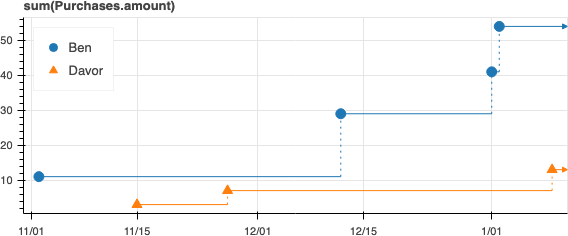

The time axis of a timeline reflects the time of a computation’s result. For example, at any point in time we might ask “what is the sum of all purchases?”. Aggregations over timelines are cumulative – as events are observed, the answer to the question changes. We call these continuous timelines because each value continues until the next change.

Compared to SQL, timelines introduce two requirements: ordering by time and grouping by entity. While the SQL relation – an unordered multiset or bag – is useful for unordered data, the additional requirements of timelines make them ideal for reasoning about cause-and-effect. Timelines are to temporal data what relations are to static data.

Adding these requirements mean that timelines are not a fit for every data processing task. Instead, they allow timelines to be a better fit for data processing tasks that work with events and time. In fact, most event streams (eg., Apache Kafka, Apache Pulsar, AWS Kinesis, etc.) provide ordering and partitioning by key.

When thinking about events and time, you likely already picture something like a timeline. By matching the way you already think about time, timelines simplify reasoning about events and time. By building in the time and ordering requirements, the timeline abstraction allows temporal queries to intuitively express cause and effect.

Using Timelines for Temporal Queries

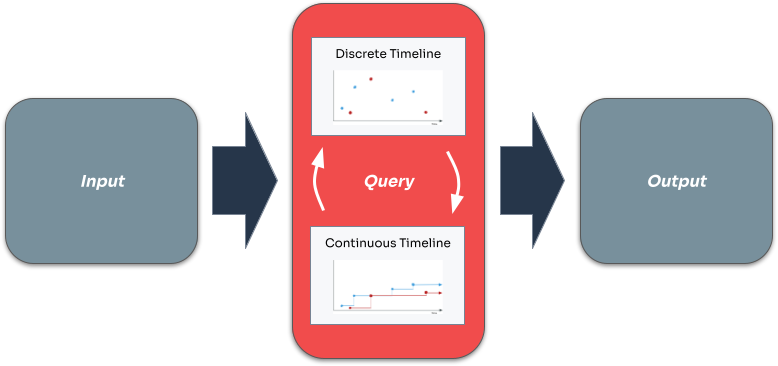

Timelines are the abstraction used in Kaskada for building temporal queries, but data starts and ends outside of Kaskada. It is important to understand the flow of data from input, to timelines, and finally to output.

Every query starts from one or more sources of input data. Each input – whether it is events arriving in a stream or stored in a table, or facts stored in a table – can be converted to a timeline without losing important context such as the time of each event.

The query itself is expressed as a sequence of operations. Each operation creates a timeline from timelines. The result of the final operation is used as the result of the query. Thus, the query produces a timeline which may be either discrete or continuous.

The result of a query is a timeline, which may be output to a sink. The rows written to the sink may be a history reflecting the changes within a timeline, or a snapshot reflecting the values at a specific point-in-time.

Inputting Timelines

Before a query is performed, each input is mapped to a timeline. Every input – whether events from a stream or table or facts in a table – can be mapped to a timeline without losing the important temporal information, such as when events happened. Events become discrete timelines, with the value(s) from each event occurring at the time of the event. Facts become continuous timelines, reflecting the time during which each fact applied. By losslessly representing all kinds of temporal inputs, timelines allow queries to focus on the computation rather than the kind of input.

Outputting Timelines

After executing a query, the resulting timeline must be output to an external system for consumption. The sink for each destination allows configuration of data writing, with specifics depending on the sink and destination (see connector documentation).

There are several options for converting the timeline into rows of data, affecting the number of rows produced:

- Include the entire history of changes within a range or just a snapshot of the value at some point in time.

- Include only events (changes) occurring after a certain time in the output.

- Include only events (changes) up to a specific time in the output.

A full history of changes helps visualize or identify patterns in user values over time. In contrast, a snapshot at a specific time is useful for online dashboards or classifying similar users.

Including events after a certain time reduces output size when the destination already has data up to that time or when earlier points are irrelevant. This is particularly useful when re-running a query to materialize to a data store.

Including events up to a specific time also limits output size and enables choosing a point-in-time snapshot. With incremental execution, selecting a time slightly earlier than the current time reduces late data processing.

Both “changed since” and “up-to” options are especially useful with incremental execution, which we will discuss in part 4.

History

The history – the set of all points in the timeline – is useful when you care about past points. For instance, this may be necessary to visualize or identify patterns in how the values for each user change over time.

Any timeline may be output as a history. For a discrete timeline, the history is the collection of events in the timeline. For a continuous timeline, the history contains the points at which a value changes – it is effectively a changelog.

Snapshots

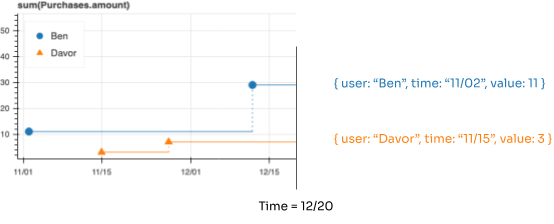

A snapshot – the value for each entity at a specific point in time – is useful when you just care about the latest values. For instance, when updating a dashboard or populating a feature store.

Any timeline may be output as a snapshot. For a discrete timeline, the snapshot includes rows for each event happening at that time. For a continuous timeline, the snapshot includes a row for each entity with that entity’s value at that time.

Conclusion

This blog post highlighted the challenges associated with creating and maintaining temporal queries on event-based data streams and introduced the timeline abstraction as a solution. Timelines organize data by time and entity, providing a more suitable structure for event-based data compared to multisets.

The timeline abstraction is a natural progression in stream processing, allowing you to reason about time and cause-and-effect relationships more effectively. We also explored the flow of data in a temporal query, from input to output, and discussed the various options for outputting timelines to external systems.

Rather than applying a tabular – static – query to a sequence of snapshots, Kaskada operates on the history (the change stream). This makes it natural to operate on the time between snapshots, rather than only on the data contained in the snapshot. Using timelines as the primary abstraction simplifies working with event-based data and allows for seamless transitions between streams and tables.

You can get started experimenting with your own temporal queries today. Join the slack community and let us know what you think about the timeline abstraction.

Check out the next blog post in this series, where we’ll delve into the Kaskada query language and its capabilities in expressive temporal queries. Together, we’ll continue to explore the benefits and applications of the timeline abstraction in modern data processing tasks.